AS 201 The Yijing 易經 or Book of Changes--

a repository of profound moral and metaphysical truths

From Richard Wilhelm,

The Book of Changes -- I Ching [ or Yijing] in Chinese -- is unquestionably one of the most important books in the world's literature. Its origin goes back to mythical antiquity, and it has occupied the attention of the most eminent scholars of China down to the present day. Nearly all that is greatest and most significant in the three thousand years of Chinese cultural history has either taken its inspiration from this book, or has exerted an influence on the interpretation of its text. Therefore it may safely be said that the seasoned wisdom of thousands of years has gone into the making of the I Ching. Small wonder then that both of the two branches of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism and Daoism, have their common roots here. The book sheds new light on many a secret hidden in the often puzzling modes of thought of that mysterious sage, Laozi, and of his pupils, as well as on many ideas that appear in the Confucian tradition as axioms, accepted without further examination.

From the Introduction to his translation, http://www.iging.com/intro/introduc.htm

Six Useful Quotes:

1. Jeelo Liu:

The Yijing, commonly translated as the Book of Changes, is the single most important work in the history of Chinese philosophy. It is not only the source of Chinese cosmology, but also the very foundation of the whole Chinese culture. Both the two leading Chinese philosophical schools, Confucianism and Daoism, drew cosmological and moral ideas from this book, which has been described as “a unique blend of proto-Confucian and proto-[Daoist] ideas.” Yijing has also penetrated the Chinese mind. Every Chinese person, with or without philosophical training, would be naturally inclined to view the world the way Yijing depicts it — a world of possibilities as well as determination; a world dominated by yin and yang and yet alterable by human efforts. [From Jeeloo Liu, An Introduction to Chinese Philosophy 2006, p. 26]

2. And, as Professor Richard Smith writes in his 2008 study of the Yijing:

There is probably no work circulating in the modern world that is at once as instantly recognized and as stupendously misunderstood as the Yijing. Although most people are aware that the Changes originated in China, few are aware of how it evolved there and how it found its way to other parts of Asia and eventually to the West. Fewer still know anything substantial about the contents of the book....It has been described...as a book of philosophy, a historical work, an ancient dictionary, an encycopedia, an early scientific treatise, and a mathematical model of the universe. To some, the Yijing is a sacred scripture, not unlike the Jewish and Christian bibles, the Islamic Qur'an, the Hindu Vedas, and certain Buddhist sutras; to others it is a work of "awesome obscurity," teetering on the brink between a "profound awareness of the human mind's capacities and superficial incoherency." [Richard Smith, Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World (University of Virginia Press, 2008), p. 1.]

3. And as the great Han Dynasty Commentator Wang Bi puts it, "Change occurs because of the interaction between the innate tendency of things and their countertendencies to behave in ways opposed to their natures."

4. Liu Yiming:

The Sages created Images to give full expression to Meaning. They constructed Hexagrams to give full expression to Reality. They attached Words to these Images and Hexagrams to give full expression to Speech...In its Resonance, it reaches the Core of the World. Through the Yijing, the Sage plumbs the greatest depths, Investigates the subtlest Springs of Change. Its very depth penetrates the Will of the World.

5. John Minford, in his recent (2014) translation, includes a helpful quote from American scholar Michael Nylan who says that the Yijing is a book "designed to instill in readers a simultaneous awareness both of the deep significance of ordinary human life and the ultimately mysterious character of the cosmic process." (xxiii)

6. Wang Bi on the complex relationship that it posits between Words, Images, and Ideas in the Changes. A Han Dynasty expert on Daoism and the Yijing, Wang Bi (226-249), is fascinating because he died so young; he was only 23 years old!

The Yijing is traditionally thought of as something that one works on for their entire life and can only begin to understand it--much less master its content--during one's advanced years. Apparently, this was not the case for Wang Bi who was some kind of prodigy or genius. [Page numbers below are from Richard Lynn's The Classic of Change, 1994]:

--Images are the means to express Ideas Words are the means to explain the Images To yield up ideas completely, there is nothing better than the images, and to yield up the meaning of the images, there is nothing better than words.

--The Words are generated by the Images, thus one can ponder the words and so observe what the images are.

The Ideas are yielded up completely by the Images, and the Images are made explicit by the words.

Thus, since the words are the means to explain the images, once one gets the images, one forgets the words, and, since the Images are the means to allow us to concentrate on Ideas, once one gets the ideas, one forgets the images….(49)

--The Changes is a paradigm of Heaven and Earth. Looking up, we use the Changes to observe the configurations of Heaven, and, looking down, we use it to examine the patterns of the Earth. Thus we understand the reasons underlying what is hidden and what is clear. We trace things back to their origins, then turn back to their ends. Thus we understand the axiom of life and death. (51)

The reciprocal process of yin and yang is called the Dao. What is the Dao? It is a name for nonbeing (wu); it is that which pervades everything; and it is that from which everything derives. As an equivalent, we call it Dao. As it operates silently and is without substance, it is not possible to provide images for it. Only when the functioning of being reaches its zenith do the merits of nonbeing become manifest …

It is by investigating change thoroughly that one exhausts all the potential of the numinous, and it is through the numinous that one clarifies what the Dao is. (53) [By numinous here we mean the spiritual, the sacred, the sublime; also, the mysterious and the holy, and the sublime.]

What did Confucius himself say about the Changes?

The Master [Confucius] said: “The Changes, how perfect it is! It was by means of the Changes that the sages exalted their virtues and broadened their undertakings. Wisdom made them exalted, and ritual made them humble. Exalted, they emulate Heaven, and, humble, they model themselves on Earth. With Heaven and Earth having their positions thus fixed, Change operates in their midst. As it allows things to fulfill their natures and keep on existing, this means that change is the gateway through which the fitness of the Dao operates.” (56)

Also, we can find these remarks:

The Master [Confucius] said: “As for the Changes, what does it do? The Changes deals with the way things start up and how matters reach completion and represents the Dao that envelops the entire world. If one puts it like this, nothing more can be said about it.” (63-64)

***

The Basics of the Yijing:

The book we now call the Yijing was originally called the Zhouyi (周易), or the Zhou Changes, sometimes just the Changes. As such, it is commonly associated with the founder of the Zhou Dynasty, King Wen (文) who reigned from 1171-1122 BCE and whose name, 文 signifies literacy, intelligence and learning. This early version of the Yijing already contain the 64 hexagrams, additional Commentaries known as the Ten Wings, and Commentaries on the Judgments.

We might think of the 64 Hexagrams and growing out of the 8 Trigrams (8 x 8 = 64) but scholars are not certain if the Trigrams preceded the hexagrams or not. Whichever the case, each of the 64 hexagrams may be thought of as a unified entity containing:

-- an Image, which captures the overall Meaning, or the “controlling principle” of the hexagram, and usually serves as the basis for

-- the Name by which the hexagram is known; and, finally,

-- the Judgment which amplifies the hexagram's meaning and on which Commentators have offered detailed interpretations.

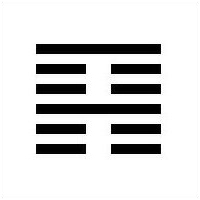

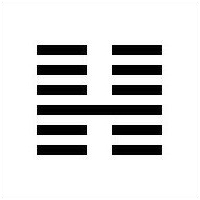

- For example, here is Hexagram #52:

-

-

Name: Keeping Still, Stopping

- Image: Mountains standing close together

- Judgment: Restraint; Keeping the back still

- The Message: "Keeping Still Means Stopping. When it is time to Stop, then Stop. When it is time to Advance, then Advance."

- Therefore, each hexagram consists of 3 important elements:

1) a Hexagram Name (guaming),

2) a Hexagram Judgment (tuan), and

3) a Hexagram Image (xiang).

Also, there is an important fourth element, Line Statements (yaoci) for each of the six lines. Since each hexagram has changing elements (broken lines) it is also in the process of converting to another, second hexagram, which also must be considered.

It is believed that all of these basic components were developed, recroded and incorporated into the Zhouyi by the 9th Century BCE.

Dating from the Early Han are the Commentaries known as the Ten Wings. "The Ten Wings elucidate the basic text of the Changes and provide it with a metaphysical framework." (Smith, p. 38)

Back in Han times, it was believed that Confucius had edited the Changes and written all of the Ten Wings himself, but now we know that this is not likely. Nevertheless, the idea that the Master had a hand in this--and he did take this work very seriously and definitely did write the Commentaries on the Judgments and the Images--was important for making Han dynasty scholars take the Changes seriously and to pay attention to it as Confucius urged. After all, it was on the top of his list of Six Books that he instructed his followers to study with dedication and seriousness of purpose.

For example, the Commentary on Hexagram 52 above reads:

艮,止也。時止則止,時行則行,動靜不失其時,其道光明。艮其止,止其所也。上下敵應,不相與也。是以不獲其身,行其庭不見其人,无咎也。

Gen denotes stopping or resting; resting when it is the time to rest, and acting when it is the time to act. When one's movements and restings all take place at the proper time for them, his way (of proceeding, 道) is brilliant and intelligent (光明). Resting in one's resting-point is resting in one's proper place. The upper and lower (lines of the hexagram) exactly correspond to each other, but are without any interaction; hence it is said that '(the subject of the hexagram) has no consciousness of self; that when he walks in his courtyard, he does not see (any of) the persons in it; and that there will be no error.'

One of the important Commentaries is called the Great Commentary (Dazhuan) and comprises the Fifth and Six Wings; it is also known as the Commentary on the Appended Judgments, and is usually included in translations of the Yijing such as that by Richard Wilhelm.

Although Richard Smith claims not to be a "believer" himself, he sees the Dazhuan as an extraordinary work, a "microcosm of the universe, duplicating quite literally the fundamental processes and relationships occurring in nature." He goes on to say that "the Yijing allows those who use it to partake of a potent, illuminating, activating, and transforming spirituality and by anticipating fully and sincerely in this spiritual experience, one can discern the patterns of change in the universe." (Smith, Fathoming the Cosmos, p. 8, adapted.)

- How does it work? Well, the Hexagrams incorporate images and features from the natural world--thunder, mountains, lakes, lightning, rivers, wind, the sun, the earth, the moon, etc.--and apply them to the social world, to everyday life situations. The assumption is that by consulting the Yijing and receiving a response in the form of a hexagram, somehow one has captured a little slice out of the flow of everyday experience, and reading the signs about that slice of experience can be very revealing.

- Famed psychologist Carl Jung wrote a foreward to his friend Richard Wilhelm's translation where he argued that clearly the "collective unconscious" was being expressed here, and he advanced the principle of "synchronicity" which he sees as diametrically opposed to causality, the way of looking at experience that has dominated western thought. Instead, synchronicity points to the "peculiar interdependence of objective events among themselves as well as with the subjective states of the observer." (Wilhelm, xxiv)

-

Jung also put great store in archetypes and believed that the Yijing could somehow point to these "unconscious psychological patterns that shape the way human beings think and act." We find archetypes expressed as symbols in our "art, myths and literature." (See Richard Smith, pp. 211-212) Having Jung write this Foreward and endorse the Yijing as a mysterious but powerful tool, was a significant boost to its being taken seriously by scholars in the west. And for a very long time, the Wilhelm translation was considered the authoritative version of the Yijing.

-

- He published his translation from Chinese into German in 1924, after living in China and studying with an expert, Lao Naixuan (1843-1921), since 1913. Wilhelm died in 1930 but when his German rendering was finally translated into English in 1950, it began to have an immediate impact and garnered a kind of cult following in America.

- The Beat writers of the 1950s had encountered it and in 1965, singer-songwriter Bob Dylan said in a wide-ranging interview, that:

- The biggest thing of all, that encompasses it all, is kept back in this country. It’s an old Chinese philosophy and religion, it really was one . . . there is a book called the “I-Ching”, I’m not trying to push it, I don’t want to talk about it, but it’s the only thing that is amazingly true, period, not just for me. Anybody would know it. Anybody that ever walks would know it, it’s a whole system of finding out things, based on all sorts of things. You don’t have to believe in anything to read it, because besides being a great book to believe in, it’s also very fantastic poetry.

- So Bob comes to the Yijing completely naive and without much context so he does not come off as very articulate about the Yijing. Yet, he was able to appreciate that it allows one to "penetrate into moments of the cosmic order" and by doing this, one can discover "what one's place in the scheme of things should be." So, even though he is not all that well informed or studied, he does seem to "get it" in a certain way in that he grasps that it opreates as a system to help people find out things and it can be amazingly penetrating in its insights.

- So, by the mid-1960s, to know about the Yijing was to be in the know, to be "hip."

- Consulting the Yijing:

- Various methods are used to consult the Yijing in order to "get" the appropriate Hexagram for interpretation--such as "throwing" the Three Coins or counting out the 49 Yarrow Stalks. This will yield an answer to a specific question. For example, if the specific question asked here that yielded Hexagram #52 had been something like "Should I Move Forward with a certain plan? then the answer clearly would have been, NO: Now is not the time to Advance. It is Not a propitious time for moving forward. It is a time for Stillness and Rest.

-

Wilhelm wrote about consulting the Yijing as follows:

The only thing about all this that seems strange to our modern sense is the method of learning the nature of a situation through the manipulation of yarrow stalks. This procedure was regarded as mysterious, however, simply in the sense that the manipulation of the yarrow stalks makes it possible for the unconscious in man to become active. All individuals are not equally fitted to consult the oracle. It requires a clear and tranquil mind, receptive to the cosmic influences hidden in the humble divining stalks. As products of the vegetable kingdom, these were considered to be related to the sources of life. The stalks were derived from sacred plants.

- But It is Not All about Divination:

- The Hexagrams also became something much more than just a mechnism for divination: they offer a way to penetrate into moments of the cosmic order and learn how the Way, or the Dao, is configured. and what one's place in the scheme of things should be. Therefore, one could study the hexagrams in many different ways, even making it a part of a daily practice of study and contemplation. The more one studies the Yijing, the more one practices and learns from the Hexagrams, the better one understands the world and one's place in it. Many believe that the Yijing is a profound Book of Wisdom, a guide to anyone following a Spiritual Path through life.

- As Song Dynasty philosopher Cheng Yi notes, "The Book of Change is Transformation. It is the Transformation necessary if we are to be in tune with the Movement of Time, if we are to follow the Flow of the Dao. The book is grand in scope; it is all-encompassing. It is attuned to the very principles of Human Nature and Life-Destiny.

- Or, as 18th century Liu Yiming says, as quoted above: "The Sages created Images to give full expression to Meaning. They constructed hexagrams to give full expression to Reality. They attached Words to these Images and Hexagrams to give full expression to Speech...In its Resonance, it reaches the Core of the World. Through the Yijing, the Sage plumbs the greatest depths, Investigates the subtlest Springs of Change. Its very depth penetrates the Will of the World. Knowledge of the Springs of Change Enables terrestial enterprises to be accomplished."

- ***

- The Yijing, then, offers us the opportunity to become self-reflexive about our lives, to be more conscious, more aware of the situations that come our way, all the while reminding us that everything unfolds in the context of a mysterious cosmic process about which we should feel a sense of wonder and awe. In his Opening Convocation last year, Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner, who studies the science of having a "Meaningful Life," investigates the neurological processes involved in being compassionate and happy; he studies what happens to us physiologically when we experience that sense of wonder and awe about life that this year's Convo Speaker, Robert Krulwich, spoke about. Keltner's research finds that awe actually leads to a sense of commonality with others which, in turn, incites felings of respect, reverence, and even humility, as people become more modest and less egotistic in the face of awe. Oddly enough, Keltner is influenced by Asian thought and uses Confucius' concept of Ren or "Benevolence," "Humanity," "Human Kindness," or "Authoritative Conduct" which he charcterizes as that deeply satisfying moment when you bring out the good in others.

he finds an indication of this path of humility in cross-cultural interpretation and the importance of finding balance:

www.academia.edu/822553/The_Yijing_and_Philosophy_From_Leibniz_to_Derrida

Integrating Words, Images and Ideas:

As we saw above, Quote #6, one of the most interesting things about the Yijing is the complex relationship that it posits between Words, Images, and Ideas. Han Dynasty expert on Daoism and the Yijing, Wang Bi, explains his views below. [Page numbers below are from Richard Lynn's The Classic of Change, 1994].

It is held that someone who stays fixed on the words will not be one to get the images, and someone who stays fixed on the images will not be one to get the ideas. The images are generated by the ideas, but if one stays fixed on the images themselves, then what one stays fixed on will not be images as we mean them here. The words are generated by the images, but if one stays fixed on the words themselves, then what one stays fixed on will not be words as we mean them here. If this is so, then someone who forgets the images will be one to get the ideas, and someone who forgets the words will be one to get the images. Getting the ideas is in fact a matter of forgetting the words. Thus, although the images were established in order to yield up ideas completely, as images they may be forgotten…(31-32)

[So, to restate, images yield up words and words yield up ideas; the key is to get to the ideas so once you take that pathway, the images themselves can be discarded because you have grasped the ideas.] It was believed some of the great Sage Rulers on Antiquity came up with the Hexagrams:

The sages set down the hexagrams and observed the images. They appended phrases to the lines in order to clarify whether they signify good fortune or misfortune and let the hard and the soft lines displace each other so that change and transformation could appear. (49)

The Judgments address the images. (50)

The Changes is a paradigm of Heaven and Earth. Looking up, we use the Changes to observe the configurations of Heaven, and, looking down, we use it to examine the patterns of the Earth. Thus we understand the reasons underlying what is hidden and what is clear. We trace things back to their origins, then turn back to their ends. Thus we understand the axiom of life and death. (51)

The reciprocal process of yin and yang is called the Dao. What is the Dao? It is a name for nonbeing (wu); it is that which pervades everything; and it is that from which everything derives. As an equivalent, we call it Dao. As it operates silently and is without substance, it is not possible to provide images for it. Only when the functioning of being reaches its zenith do the merits of nonbeing become manifest …It is by investigating change thoroughly that one exhausts all the potential of the numinous, and it is through the numinous that one clarifies what the Dao is. (53) [By numinous here we mean the spritual, the sacred, the sublime; also, the mysterious and the holy, the sublime.]

Note: The interesting thing about Wang Bi (226-249) is that he died so young; he was only 23 years old! The Yijing is traditionally thought of as something that one works on for their entire life and can only begin to understand it--much less master its content--during one's advanced years. Apparently, this was not the case for Wang Bi who was some kind of prodigy or genius.

See some more helpful references to the I Ching/Yi Jing online such as:

http://www.iging.com/

http://www.eclecticenergies.com/iching/virtualcoins.php

http://www.wisdomportal.com/IChing/IChing-Wilhelm.html

http://www.ichingonline.net/index.php

http://pages.pacificcoast.net/~wh/Index.html

http://www.biroco.com/yijing/links.htm

http://www.yjcn.nl/wp/

http://www.biroco.com/yijing/zhouyi.htm